Concrete Dreams: Celebrating the Southbank Centre’s brutalist buildings

In 2018, as our brutalist buildings reopened following refurbishment, Dr. Otto Saumarez Smith, Shuffrey Junior Research Fellow in Architectural History at Lincoln College, University of Oxford, took a closer look at the history and architecture of these brutalist icons.

Do buildings have memories? If concrete were conscious, the buildings of the Southbank Centre would remember playing host to an astonishing range of events. In the half century since the Queen Elizabeth Hall was built in the late 1960s, this beautifully brutal concrete megastructure has reverberated with many artistic eruptions. What trace remains from a concert once the applause has died down, the audience has departed, and instruments are packed away? What is left from an exhibition once the artworks have been taken down?

The crucial legacy of the Southbank Centre is in memories: in the recollections of the architects, builders and craftspeople who gave these structures form; the artists, performers, technicians, and programmers who filled these spaces with art and music; but most importantly in the enjoyment of audiences hungry for new experiences, inspiration, and delight. These buildings were made for artists and audiences, and it is people who give them life.

The 2018 exhibition Concrete Dreams celebrated the re-opening of a complex of bold, sometimes controversial buildings, as they re-inhabited their role at the heart of London’s cultural life after over two years of refurbishment. Somewhere in between the permanent building and the intangible memories of users, the exhibition presented the treasures left behind by an astonishing artistic programme: showcasing the posters, recordings, press cuttings, autograph books and more, that make up an evocative archive full of tales and personal accounts.

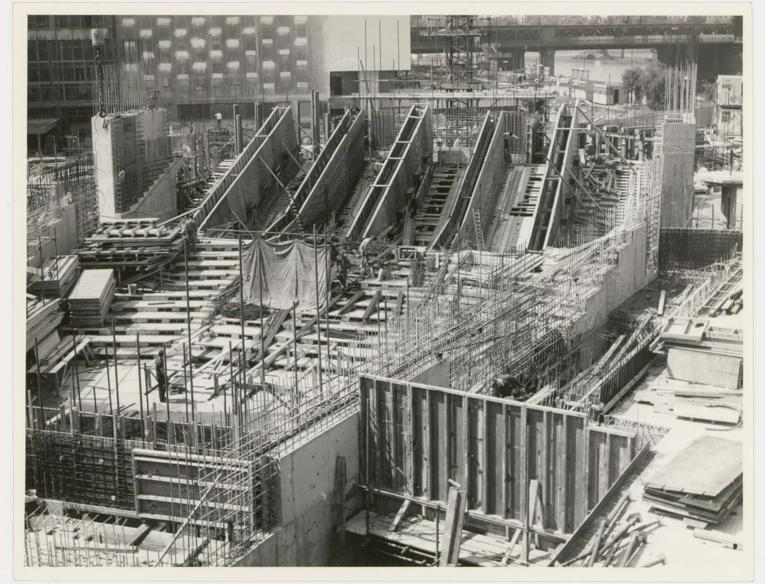

Opened in 1967-68, the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room and Hayward Gallery joined the already existing Royal Festival Hall to create a powerhouse of artistic provision. At the end of the Second World War the Thames-side site, despite its glorious views across to the Houses of Parliament, was little more than a derelict industrial wasteland. The 1951 Festival of Britain had transformed the area, but it was short lived, with most of its structures removed when the incoming Conservative government came to power in later that year – leaving Royal Festival Hall standing in a wasteland. Plans for the additional buildings were revealed in 1961, with work beginning in 1963.

This complex of buildings was designed by a group of radical young architects led by Norman Engleback, working for the London County Council, which then housed the world’s largest architectural office. They were given astonishing freedom to innovate, although the entire team was brought to the brink of resigning when their experimental and radical ideas were threatened. The architects approached the project from the inside out, with the exterior a secondary consideration to the requirements of the concert halls and galleries.

The buildings are a result of an almost symphonic collaboration, bringing together a whole range of participants and viewpoints: from bureaucrats from the London County Council, to officials from the Arts Council of Great Britain, to the construction company Higgs and Hill, and the engineering firm Arup, as well as input and guidance from acousticians, artists and musicians including Henry Moore and Yehudi Menuhin.

The structure that resulted from these collaborations is a thrilling hodgepodge of sprouting mushroom columns, jumbled geometries, cantilevered cubes, and precipitous terraces. All of these elements tie together with an upper-level podium, out of which the buildings rise like dirty icebergs. The architecture is often contrasted with that of the neighbouring Royal Festival Hall as being emblematic of the difference between the architectural culture of the 1950s and of the 1960s; between the ‘herbivores’ and the ‘carnivores’ as the playwright Michael Frayn put it.

Royal Festival Hall is elegant, spacious and sophisticated whilst the 1960s buildings, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room and Hayward Gallery, are rebellious, inward-looking and sculptural. All however are beautifully conceived and executed buildings, offering superb performance spaces, and providing a sense of theatre and occasion to the way people circulate through them; they are only completed by people using them.

Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room and Hayward Gallery are outstandingly detailed throughout, and were the work of hundreds of highly skilled craftspeople. Concrete can have a bad reputation, and it is often perceived as uniform, ugly and alienating. The cool grey board-marked concrete of Southbank Centre’s 1960s buildings belies these perceptions – hand-made, sumptuous and haptic. The concrete was poured into moulds of Baltic pine, reproducing the rough grain of the wood, a technically demanding process: the building has been described as a wooden building, but cast in concrete.

Along with the board-marked concrete, much admired for its distinctiveness, the Southbank Centre boasts external precast panels made with crushed Cornish granite, cast anodized doors and window frames, aluminium seats formed using a technique borrowed from the aircraft industry and cushioned with elegant black leather, crystalline white Macedonian marble floors, and polished brass handrails. The rough tactile poetry of these restrained materials are really able to sing again in architects Feilden Clegg and Bradley’s renovation: they have worked with, rather than against the (concrete) grain of this 1960s masterwork.

“When you see the hard cold concrete of a brutalist building, they can look very inhuman, like a machine-made building. But if you stop and think about how they were actually made you start to realise that really they’re a very deep expression of the craft involved in making them.”

From the early years the programme of Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room were distinguished by their astonishing diversity, reflecting an era that saw a huge expansion of what constituted culture. Events ranged from the classical to the countercultural, from folk music and jazz to rock and pop. They pushed boundaries, ignoring censorship and giving early exposure to many musicians and artists who would go on to become household names, such as the summer music series put on by Daniel Barenboim, then only 25, as an alternative to the Proms.

Indian classical music was also a mainstay of the programme from the early days, with concerts by Imrat Khan, Surya Kumari and others. Southbank Centre was the location of many pioneering moments in the history of the English Folk Revival and Electronic music with acts such as Delia Derbyshire and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. 25 June 1973 saw the first outing of Mike Oldfield’s epic Tubular Bells. David Bowie, T Rex and Pink Floyd all had early concerts in the Queen Elizabeth Hall building. Poetry International, Southbank Centre’s longest running festival, was set up by future Poet Laureate Ted Hughes in 1967, to celebrate what he saw as poetry’s ability to be ‘a universal language of understanding in which we can all hope to meet’, a mission the ongoing festival continues to uphold.

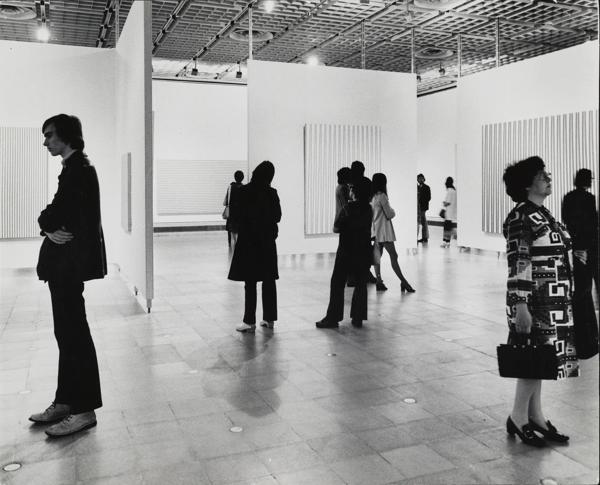

At the time, neither the Tate nor the National Gallery were able to hold temporary exhibitions without displacing part of their permanent collections, so Hayward Gallery immediately filled a vital lacunae in London’s art world. Early pioneering shows included the first solo large-scale UK shows by Bridget Riley and Anthony Caro, whilst the arrival of British conceptual art was celebrated in the exhibition Kinetic Sculpture and the New Art.

Dennis Crompton, one of the rebellious young architects who designed Southbank Centre, argued that ‘People don’t fall in love with the buildings; they fall in love with the things made possible because of the buildings.’ Concrete Dreams served as a love letter to these buildings, and all the wonderful things that were made possible because of them. It gave an opportunity to look back, but also to take inspiration from 50 pioneering years, and look forward to a continuing legacy where these concrete buildings continue to play host to concrete dreams.

“People don’t fall in love with the buildings; they fall in love with the things made possible because of the buildings”