Poetry Games: Playing with words

Poetry is much more than words on a page. Something which is particularly starkly illustrated in the National Poetry Library exhibition, Poetry Games.

Opening to coincide with this year’s London Literature Festival, Poetry Games is an exhibition of interactive games and puzzles that bring together the worlds of poetry and play. From books of prompts to playing cards, to distinct dictionaries and even, well, a lemon in a box, these games are designed to open up your creativity and take a different approach to the words of the world around you.

To give you a flavour of what you can expect from the exhibition, seven members of the National Poetry Library team kindly took some of the interactive games from the library's wider collection for a spin.

Content is Never Less Than A Dissolution of Form by Thomas A. Clark

‘I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the concept of play, which can constitute the act of experimenting and making a mess for the sake of the experience of making a mess. I also think about how this is connected, and maybe even dependent, on our proximity to feelings of safety. What happens when we let go of the rules and self-restraint that keep us from danger? What happens when danger and critique is out of our peripheral and we’re able to exhale?

‘I am reminded of this when I look at Clark’s piece, which I see to be a take on how far we can stretch our definitions of form, content, and sensuality. To expand our understanding of these terms and our ability to apply them to our artistic practice. I also wonder what space he was in to create this piece, and if he felt the freedom to create without the looming feeling of judgement or criticism. Also, this lemon smells great.’

Troy Cabida

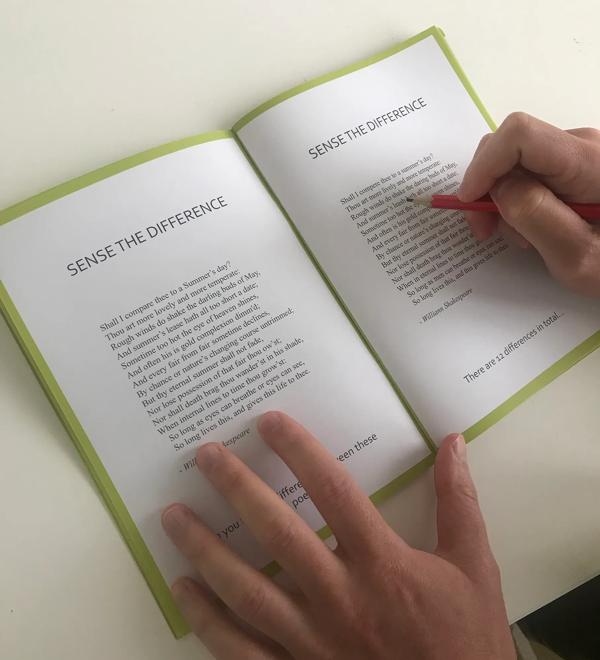

Oulipo Puzzle Book by Trickhouse Press

‘Launched this year by Trickhouse Press, The Oulipo Puzzle Book series contains puzzles – including anagrams, mazes and crosswords of varying difficulties, as well as entirely new puzzle forms – inspired by Oulipo, a movement in which writers used linguistic constraints to shape their work.

‘One of the most inspiring things about this new series is that it invites readers to interact and have fun with a genre that may often be perceived as esoteric or intimidating, opening it up to new audiences through the medium of play. And it manages to do this without sacrificing any of the genre's inventiveness or innovation. Through puzzles, readers are encouraged to participate in the creative act of Oulipo, opening possibilities for a new kind of poetics that is convincingly proposed in editor Dan Power's introductory note; ‘the poem is the process... the poetics is the act of puzzling itself’.’

Will René

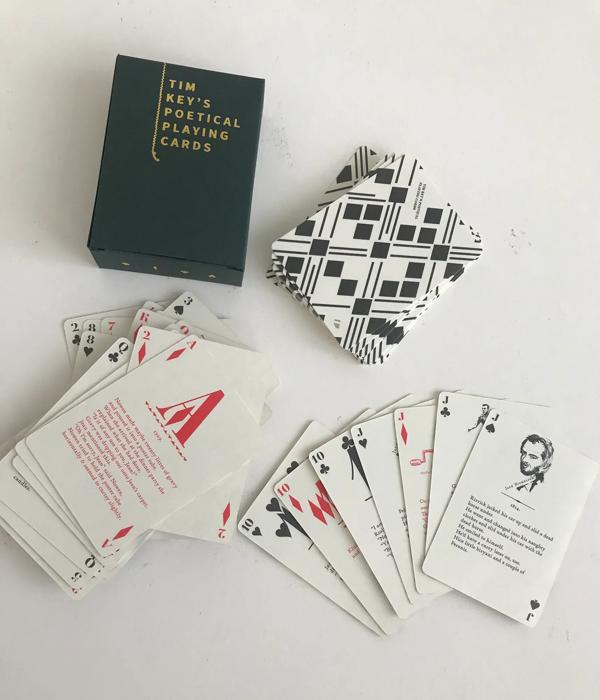

Tim Key’s Poetical Playing Cards

‘These Poetical Playing Cards are a collaboration between illustrator Emily Juniper and poet, comedian, actor and screenwriter Tim Key. Bringing his trademark absurdist humour to a pack of cards, he describes them as ‘disconnected, irrelevant, and scattergun with a format that is perfect for the material and decadent paper stock’. Containing a single blue flamingo, fragments of fictional conversations and poems, all within a gold foiled box, this pack of cards is not only a beautiful object but a vehicle to play perhaps the slowest and silliest game of cards of your life.

‘As I play a game of rummy with fellow Library Assistant Elspeth Walker, we laugh about how nonsensical the poems are, how their anarchic freedom contrasts with the rules inherent in playing a game of cards. Clearly inspired by Soviet-era Russian absurdist poet Daniil Kharms, Key’s poem fragments are anti-narrative, with wild leaps from one line to the next providing no explanation of how his often unfortunate protagonists end up where they end up. Reading the cards feels a bit like being booby-trapped or slapped unexpectedly by a stranger. Although this might sound unpleasant, you actually end up laughing… a lot! Plus it features Jack Nicholson as the Jack of Hearts; win win.’

Emily Wood

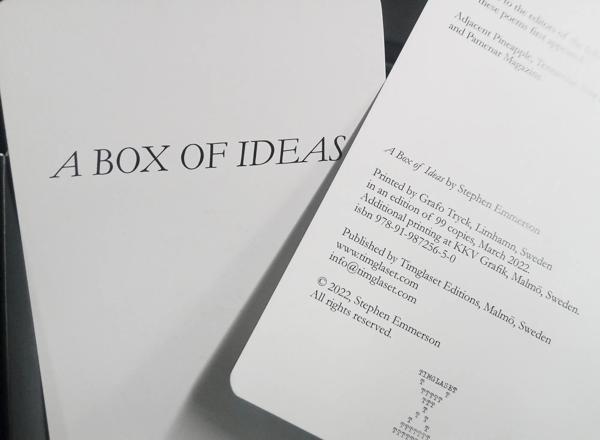

A Box of Ideas by Stephen Emmerson

‘Alone and game for Solitaire, Devil’s Grip, or The Idiot? The suits of this deck offer alternative enrichment (sadly not financial) in the form of blinker-busting inspiration for a long-frustrated desire to pen an entire book of poems without even breaking a sweat.

‘Like a wardrobe of costumes, these prompt cards act as ways to dress up the imagination in startling fancy modes and means, including faithful transcription of text-message typos, the leavings of tea, and cats’ paws on keyboards. Words? So Old School. Here be poetry made of weather, saliva, insects!

‘Still stuck? The idea I found most inspiring was one nestled, almost hidden, at the back – Writing not Writing – in which every page describes something that serves to distract the writer from actually doing any writing. Plenty of material there.

Karen Smith

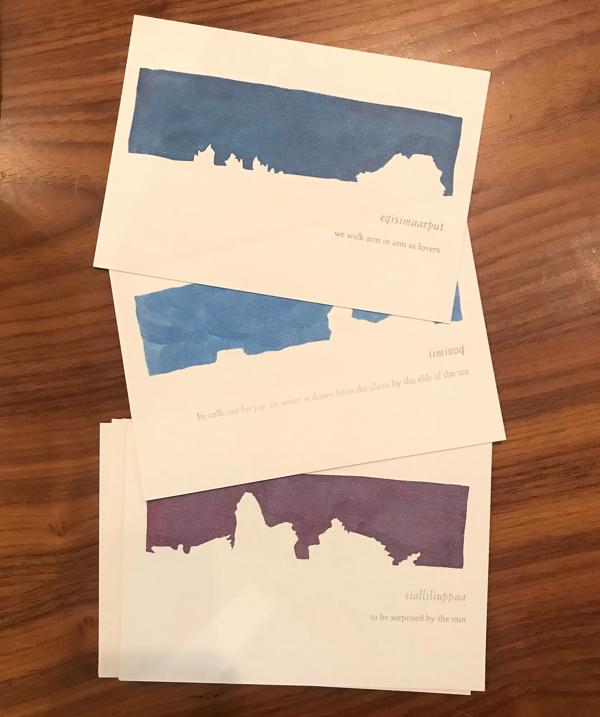

How to Say ‘I Love You’ in Greenlandic by Nancy Campbell

‘This is one of my favourite items in the library, but I haven’t looked at it closely for years. It reminds me of the memory card games I used to play when I was little; shuffling and reshuffling cards on my bedroom floor. Sure enough, on one of the cards, Campbell describes a card game she played as a child that influenced the form and shape of this work – one where each card showed a fragment of a continuous landscape. The horizon line at the edge of one card joins up with the next, and so on.

‘On each card: a word in the Kalaallisut language, and underneath, a poetic definition in English. The soft screen-printed colours resemble Arctic cloudscapes, with sharp glacial shapes stencilled out of white space. As I examine each card, the colour of the sky I’m looking at changes from butter yellow to lilac to hot orange.

‘I lift them one at a time from the deck – and since they can be read in any order, I reorder them in my hands, then spread out two rows of cards on the table in front of me. In doing so, I’ve created a continuous horizon. A spontaneous found poem emerges, made up of chunks of floating ice…’

sialliliuppaa

to be surprised by the rain

puttaarpoq

he leaps from one ice flow to another, or, he dances

Nina Powles

Tiny Jenga by Astra Papachristodoulou

‘Tiny Jenga was one of the first introductions I had into the library's collection of object and game poetry. The game is played just like Jenga, with a twist of each block having words on two sides, which, as you carefully deconstruct the Jenga tower, collates to form a new poem block. Reading from the bottom up, it’s a great game to expand on how we view poetry, both as a collaborative thing, and a physical process.

‘Playing with Assistant Librarian Will René also made me realise that poetry can be competitive. It also reminded me that the process of making poetry is as important as the final work. We ended up being more focused on making sure we weren’t the one to topple the tower on each turn, rather than the words we were choosing at first. The tower of phrases and words kept growing, and as we became more aware of the shape the poem was taking, we started to notice what we could pick next. In the end I sadly went too adventurous with my choices of block and it tumbled down. What was left was a collective poem, or if you preferred a fresh collection of words to create a framework for new writing.

‘I’ve always loved Papachristodoulou’s work, ever since I saw the Tiny Jenga, and delved further into her output. From visual poetry, to object work, and creating word games, she’s a fresh voice in the writing world, expanding how we present and create work, with a splash of fun to open it up to all.’

Elspeth Walker

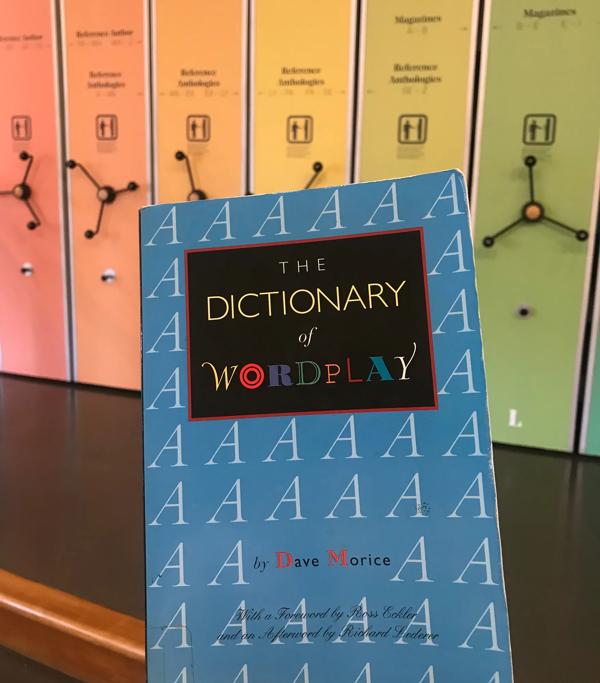

Dictionary of Wordplay by Dave Morice

‘Dave Morice's Dictionary of Wordplay is essentially an annotated list of trivia and ludic ideas involving the shapes of words and sentences: palindromes, pangrams and a hefty dose of Oulipo. It’s full of fascinating stuff.

‘I learnt, for example, about the zzyxjoanw hoax, wherein a made-up word in a dictionary of musical instruments lay unspotted for half a century. I spent a while squinting at the Universal Letter – a monogram that embodies all the letters of the alphabet, and I was interested – not to say surprised – to read that in England the 'customary greeting' when answering the phone is 'Are you there?'

‘Several of the entries are poetry-related. I wanted to try one – preferably one that would take me less than five years – and finally plumped for a spot of anagrammatic verse. In my version, every line was an anagram of my name. The resultant work was about Rose and Elmo, lovers fated to remain apart, who live somewhere that’s part-Jabberwocky, part-Surrey and whose journey involved MPs, LPs, slums, plums and munros.’

Russell Thompson

Explore these and more interactive poetry games at the National Poetry Library exhibition which runs from 21 October 2022 to 15 January 2023.