Raven Leilani on Luster & a love of language

One of the most exciting literary talents to emerge from the US in recent years, Raven Leilani’s work has been published in Granta, The Yale Review, and The Cut among other publications.

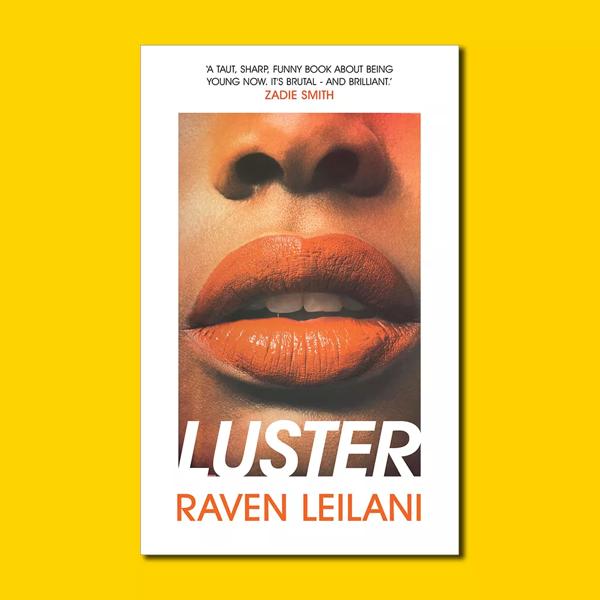

And now, following its recent UK publication, we’re finally able to enjoy her acclaimed debut novel, Luster. The book, which has earned Leilani the 2020 Kirkus Prize and Center For Fiction first novel prize, follows Edie, an engaging character deftly described by the writer and poet Monet Patrice Thomas as ‘a black woman allowed the simple privilege of fucking up without mortal consequence’.

Edie is messing up her office job, sleeping with all the wrong men, and failing at the only thing that meant anything to her: painting. But then, she meets Eric. And as if navigating the landscape of sexual and racial politics as a Black woman wasn’t hard enough, Edie finds herself falling headfirst into the home and family of this white, middle-aged archivist.

Later this month we welcome Leilani (virtually) to the Southbank Centre for an exclusive broadcast talk with Diana Evans. Ahead of that conversation we managed to have a pre-talk talk and get an early insight into Leilani’s writing process, and what the publication and success of Luster has meant for her.

It’s been six months now since Luster was first published in the US. Has its success sunk in yet, are you still feeling ‘deeply uncool’ about it?

I’m still feeling deeply uncool about it, in that it feels new every day, still. A lot has happened to me this year, professionally and personally, and I’m going to need more time to process it, definitely. I’m an introverted person, so I’m rarely at the site of the action, more comfortable on the periphery, so that has been a trip, feeling this excitement around my work. It’s amazing to me. It will never not be amazing.

When writing Luster did you have an audience in mind, or, as a first novel, were you more writing for yourself?

I always write for myself. I have to be really invested to push through a book, and my attention wanes very easily, so if I’m interested enough to sustain a project, it feels like a miracle and I have to lean into it. If I don’t have the excitement, I can’t write. Or I can, but the boredom will be felt in the prose. Though I do want to be generous. I always want to make an effort to welcome a reader in, with clarity, with deliberate structural choices.

‘I always write for myself... If I don’t have the excitement, I can’t write. Or I can, but the boredom will be felt in the prose’.

I’ve read, in another interview, of your want ‘to be vulnerable on the page’. It’s a welcome approach that delivers characters with real depth, but how do you manage to write so consistently from a place of vulnerability? Do you need to be in a specific place to be able to access that vulnerability?

This is connected to what I was just saying, about writing for myself. I mean that I have to write from love, but also that it’s imperative not to let too much outside noise in, so I’m free to write with less anxiety or embarrassment. I’m lucky in that the moment I come to the page, I feel safe, almost outside of time, and so the privacy which allows for vulnerability is just something I can click into, but I physically have to be by myself, at home. It’s only after the fact when I come up for air or the work is in the world that I think, my gosh, what did I do!

That vulnerability on the page can be seen in Luster’s depictions and descriptions of sex – something which in literature too often verges between the horrific and the unintentionally hilarious. Not only have you done it well, you’ve done it in a way where it merges the exotic and the everyday; did that come easily? Was it an intentional projection?

It was a mission I had, to totally exploit the weird machinery of the body. Everyone is privately familiar with that kind of obscene beauty and so in a way, it felt like elaborating on a secret that everyone knows. But to be very honest, it comes naturally. When I write, I feel no shame, which is an enormous departure from how I am generally in the world. I think that’s part of why I love writing so much and why when I do it I feel I need to go absolutely ballistic, because it’s one of the very few places I can be so abject.

Your characters keep the audience on their toes throughout, but so too does the structure of the book, switching from staccato to long breathless sentences. Is playing with prose in this way, something you particularly enjoy?

I do really love it. I’m grateful so many of my readers were willing to go for that ride with me, which was fun for me, but I hoped, fun for them too. I love language and rhythm and compression, and I’m always writing toward that joy, in me and in the text. I also am horrible at transitions, and you’ll notice that those sections tend to happen when I need to hurtle through time.

As well as an author, you are also – like Edie – a painter. To what extent do you feel these artistic forms of painting (and portraiture) and writing overlap?

I think they overlap in that painting, my first love, taught me how to fail. How it feels when desire surmounts the failure, which it did with writing. I think in the actual craft, there is overlap in that both require a studiousness, a love for and adherence to the hard, mundane details.

‘I love language and rhythm and compression, and I’m always writing toward that joy, in me and in the text.’

Now, after the success of Luster, you’re a full-time writer. Is there a pressure in this, or is it a welcome freedom to get more ideas onto the page?

Honestly, I’m just incredibly grateful for this privilege. I have been striving for it the entirety of my adult life with no real expectation it would happen, so it is a beautiful thing to me. If there’s any pressure, it’s that I still remember what it was like to have no time, to be exhausted and chipping away at a draft between jobs, and so now, I feel a responsibility to do everything I can with this time. It’s precious.

Interview by Glen Wilson

Hear more from Raven Leilani as she joins author Diana Evans in a special broadcast conversation, recorded exclusively for the Southbank Centre, on 25 February